The End of The Twitter Era

I've been thinking a lot about how social networks die, these past two years. It's an unusually personal topic. In 2009, I picked up my life to move to San Francisco and work for Twitter. I joined a startup you could fit around a giant lunch table, and left a corporation with thousands of employees and hundreds of millions of users.

I resigned from Twitter ten years ago, but the company will always be an important chapter in my life. Watching its decline, my mind keeps returning to a graveyard of networks past.

Friendster was my first relationship with social media, a summer fling of 2003. Technical problems knocked the site offline, letting MySpace swoop in to overtake it before it could set down roots. Facebook launched one year later, and despite a superior product, it took four years to overtake MySpace. How could that one year head start create so much friction for Facebook?

Silicon Valley ascribes this to network effects. The idea goes that as a service gains more users, the value of that service increases. AirBnB isn't valuable due to its technology— it would be trivial to clone the website. AirBnB is the eight million listings and 150 million users. Clones starting from scratch are useless, which is why venture capitalists love to invest in these de-facto monopolies.

As long as there was Twitter there were Twitter killers. Pownce (2007) allowed you to attach files, events, and links to your posts. Google tried to get in on the game with Google Buzz (2010) and Google Plus (2011), which integrated with your existing Google account. App.Net (2012) capitalized on a backlash around third-party clients. Every clone came out of the gate with solid momentum, only to crash into a wall of network effects. Users always returned to Twitter.

This time, things feel different. Two years after the takeover, we have not one, but three thriving Twitter replacements. Following the election this month, Bluesky pulled into the lead, with upwards of one million signups every day. These new services seem to stick.

If this momentum continues, things will feel less like the slow decline of MySpace, and more like the sudden shift from Digg to Reddit.

Digg was founded in 2004, and Reddit followed six months later. Reddit failed to break-out, so it was sold to Condé Nast for $10 million in 2006, a disappointing exit given Digg's talks of a $200m acquisition by 2008. When startups sell to big companies, you assume their best days are over, but in 2010 Reddit exploded in popularity after a massive backlash against Digg's product changes.

What happened to network effects? Will Twitter see a slow death like MySpace, or a sudden collapse like Digg? Can a successor live up to its legacy? I'll spoil that question right now: No, because Twitter's time has come and gone.

Since I resigned from the company ten years ago, I generally avoid writing about my time there, partly because it's unhealthy to dwell on your past, and partly because I couldn't look back without personal feelings getting in the way.

At the same time, I learned a lot in my time there. I witnessed first-hand how small changes dramatically accelerate growth. I was there for the battles between Twitter and Facebook over the social graph. I was personally involved in quite a few backlashes. With ten years of distance, maybe I'm ready to unpack some lessons.

Metcalfe's Law

Can you measure the power of a social network with a concrete number, like the "XP" of a character in a role playing game?

You could count the people who use the site every month. That's good enough for publicly traded companies to disclose in their quarterly filings. However, active users counts can be deceiving.

When an app goes viral, millions of people can sign up, spend five minutes checking it out, only to shrug and move on, never to return. In big tech lingo, those users churned, and churn was Twitter's worst enemy. Sure, breaking news and big name celebrities gave the platform unbelievable free publicity, which drove sign ups, but a ton of those signups churned.

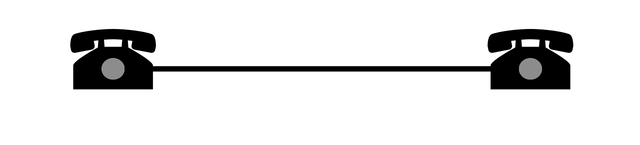

We have a better measure of a social network's value, and we owe it to Bob Metcalfe, a key figure in the history of the Internet. Metcalfe invented Ethernet, among other things. In 1980, he made a groundbreaking observation about computer networks that's often applied to social networks: the value a network isn't the nodes (or people) but the connections between the nodes.

The telephone network is a perfect example, because everyone who joins the network can call anyone else. I can call one of my cousins in Boston just as easily as I can call a stranger Lesotho. When there are two nodes in this graph, there's only one connection:

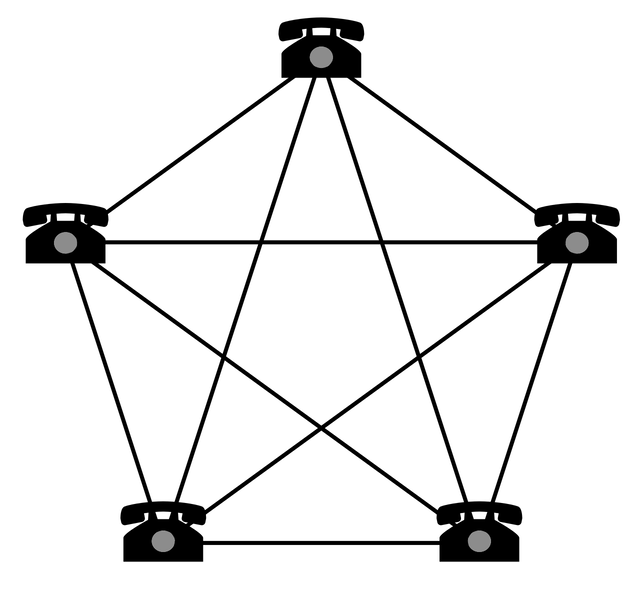

When there's five nodes, there's ten connections:

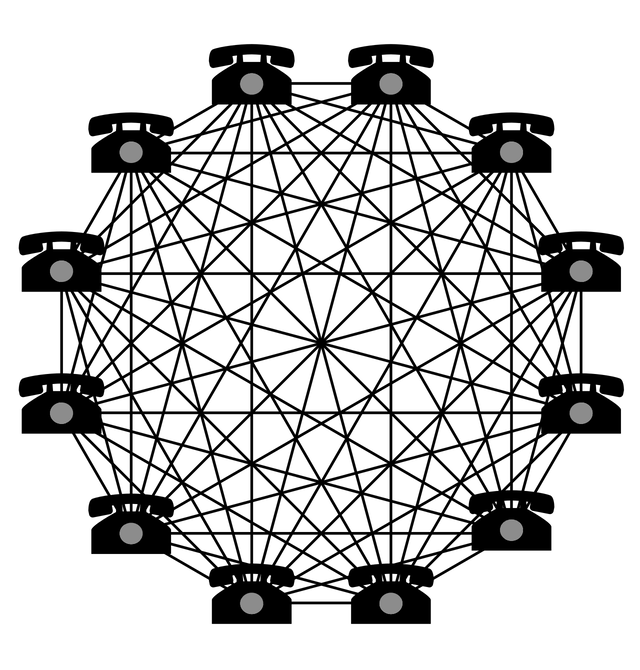

When there's twelve nodes, that's 66 connections

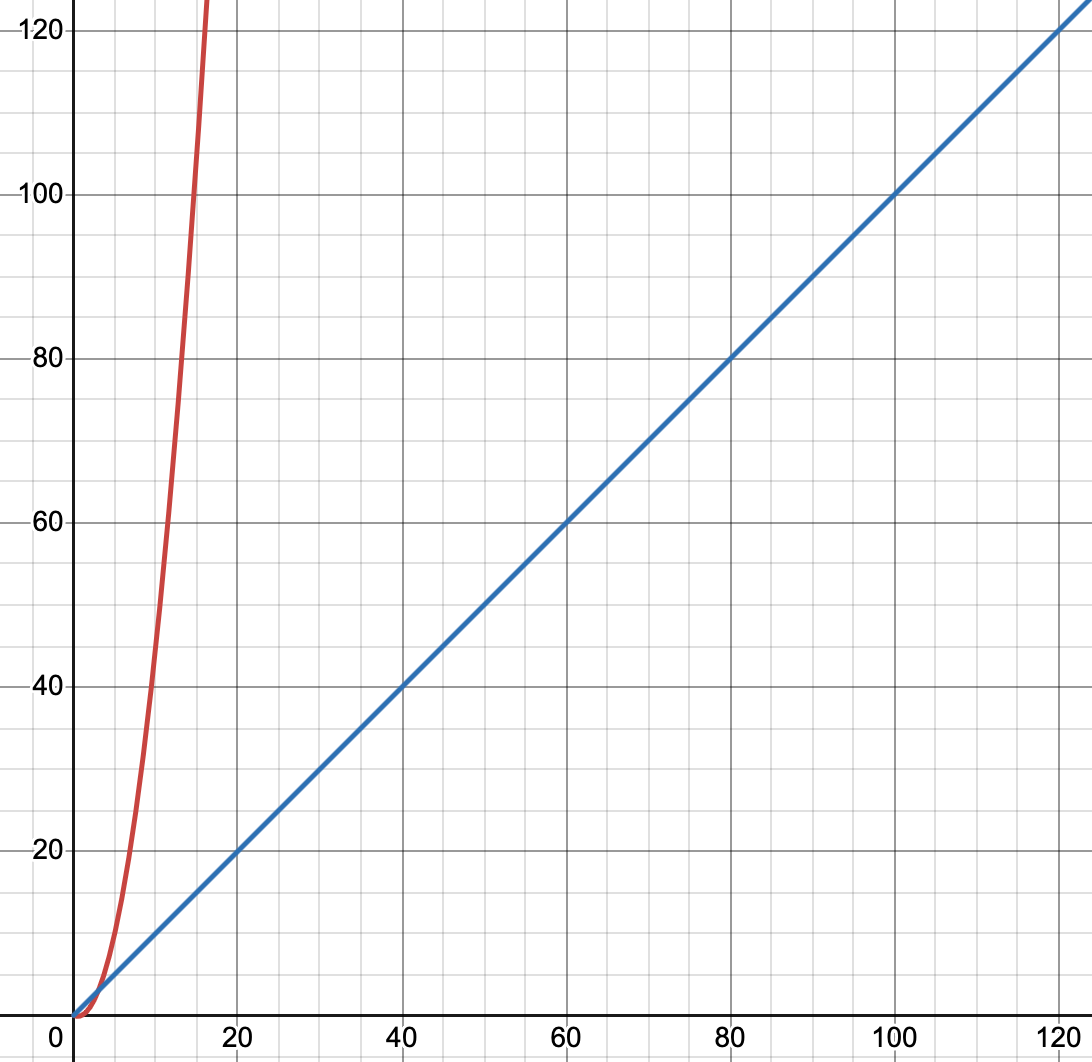

This means that the value of a fully connected network scales at N * (N - 1) * 2.

If you tried to spin up a rival phone network, capturing 1% of users wouldn't capture 1% of value. You may offer as little as 0.01% of value.

WhatsApp is a near-perfect example of this phenomenon. It dominates messaging outside of the USA, and there's little hope of disrupting that short of government intervention. Viewed under this lens, Facebook's purchase of WhatsApp for $19 Billion makes perfect sense.

That said, the average venture capitalist possesses the intellect of an airport book, and they love to throw around Metcalfe's Law to justify the absurd valuation of their latest startup. I think Metcalfe's Law points in the right direction, but it's so overused that it becomes a thought terminating cliché.

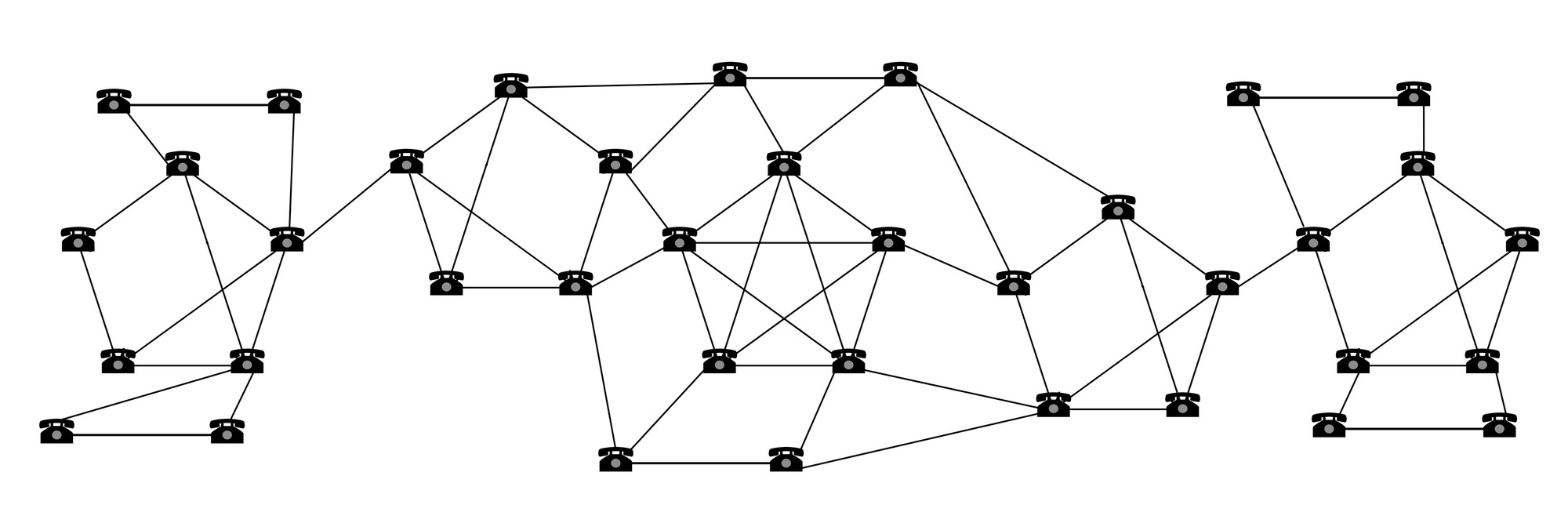

Social networks are not fully connected graphs. Facebook's entire selling point was that you aren't connected to everyone, just your friends. When you look at 66 connections on a social network, they don't look like that dense network of twelve users from earlier. 66 connections looks closer to this:

Sure, my old college improv troupe are densely packed bestie's, but we're all several degrees away from anyone in Lesotho.

In computer science, we call this a Sparse Network and it has serious implications around the strength of your network. If you lose key connectors in the graph, the network fragments into smaller, weaker, subnetworks. Compared to moving the world off telephones or email, it's pretty easy to move your closest friends and family from Facebook to private group chats.

To counter this, every social network goes out of its way to connect you with other people, whether you want to or not. When Facebook notices that a lot of your friends follow someone and you aren't, you see them in one of those "People You Might Know" boxes, to help Facebook fill out its graph. Fun fact: I have a lot of actor friends, so I sometimes get suggestions for celebrities I've never met.

In the late 2000's, building your graph was a slow process that involved manually searching for friends. This made Facebook's social graph its most valuable resource— a resource it guards with its life.

Twitter tried to expand its graph by building a web-app that connected to Facebook to help you find those same friends on Twitter. When Facebook got wind, they pulled the plug. Apple built a similar tool for their ill-fated Ping, and Facebook also shut them down, knowing it would trigger a Cold War.

The iPhone freed the social graph from Facebook's clutches. Once apps could upload their address books with one tap, it became trivial for new platforms to bootstrap their own graphs. This gave us networks like Snapchat and TikTok, to say nothing of smaller, hobbyist networks like VSCO, Goodreads, or Strava.

Another flaw with Metcalfe's Law is that not all connections are created equal. If you believe Dunbar's Number, a person's maximum number of meaningful relationships tops out at 150. That implies that social networks actually scale more linearly than exponentially, and they aren't as bulletproof as their investors would have you believe.

Different Types of Graphs

So we have WhatsApp, which is a pure network; Facebook, which is sparse; and then we have interest graphs like Digg and Twitter which are not only sparse, but one-way. Big yikes.

Many connections on these networks are lopsided, with single accounts followed by tens of thousands to millions of followers. To put this in terms even a VC can follow, these people are super-connectors.

Super-connectors are unavoidable in interest graphs, and while they're boon for growth, they also present a risk. If these connectors go elsewhere, their followers… well… follow. That's all to say that losing Taylor Swift would be catastrophic.

Super-connectors are also responsible for one network effect impossible to synthesize in a lab:

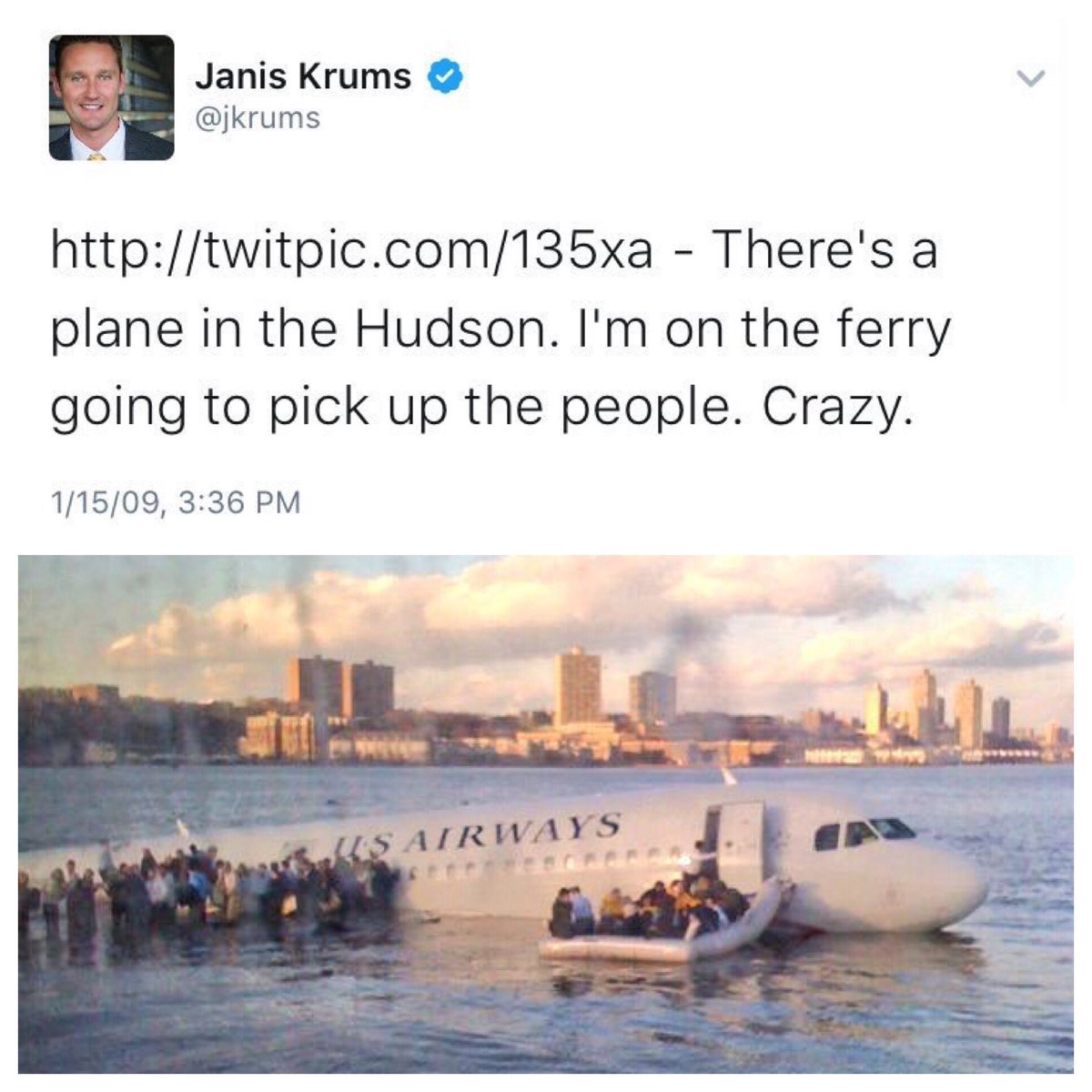

In January of 2009, the Miracle on the Hudson defined Twitter as the platform for breaking news. It was no longer just a website for nerds to live-tweet to each other as LOST aired. It was now part of the global conversation. It was the moment I knew I had to work at Twitter.

This moment happened two and a half years into the company, and it could only happen thanks to millions of users, with super-connectors helping spread the story round the world in seconds.

Network effects do not make a service invincible. Twitter is 40% social network, 40% interest graph, and 20% cultural phenomenon. So I'll place Twitter's decline somewhere in between Digg and MySpace. We may only be partway through a multi-year process, but if Twitter loses its super-connectors, I think things will quickly accelerate.

Slowly, Then All at Once

Network effects create powerful inertia. To maintain control of their lead, the incumbent network just needs to evolve its product at a reasonable pace. In retrospect, the deaths of MySpace and Digg were completely avoidable.

In 2005, News Corp acquired MySpace. According to former employees, News Corp focused on making money instead of competing with up-and-comer Facebook. This lines up with how my friends and I felt at the time, as users. There were legendary cross-site-scripting hacks, obnoxious ads, and because users could radically customize their page, the whole site felt cheap and janky.

It doesn't have to be more complicated than, "MySpace stopped being fun." Eventually, the people in my friend network woke up and realized that a switch to Facebook was less painful than putting up with the spam, hacks, and profile pages that auto-play Evanescence.

In contrast, when Facebook saw Vine as a threat to Instagram, it quickly launched video support, stopping Vine's growth dead in its tracks. When Facebook saw Snapchat as the next threat, it quickly launched Instagram Stories. When Facebook accepted WhatsApp was an unstopped force, it quickly whipped out its checkbook.

That's not to say all product changes move things in the right direction. In 2008, Digg was on top of the world. They proceeded to make a series of bad product decisions, such as its obnoxious Digg Bar. These misfires may not kill a site, but it starts conversations like, "Where should we go if things get out of hand?" When Digg's 2010 disastrous redesign launched, everyone knew where to go.

Twitter was long criticized for slow evolution, which was rooted in fear of driving users away. Until the takeover, its most unpopular changes involved killing third-party clients. With each backlash, the company caved, and came up with ways to keep the most popular third-party clients around.

Most new Twitter products landed with a "meh," such as its answer to Snapchat Stories, Fleets. Every once in a while, they shipped a real banger like Twitter Spaces, which successfully destroyed Clubhouse, a Silicon Valley darling once valued at $4 billion.

Since the takeover, almost every product change has ranged from flop to disaster. Just like News Corp did to MySpace, new leadership focused on making money. The made cuts to the Trust and Safety department which saturated the platform with scams, porn bots, and hate speech.

The new "Twitter Premium" made matters worse. Putting verified badges up for sale made impersonation trivial. Premium accounts received algorithmic boosts, allowing the worst users to pay money to have their speech amplified. Paying users for page views further incentivized rage bait.

If you ask someone to name an improvement to Twitter over the last two years, they'll probably say Community Notes, a feature built almost two years before the takeover. This feature receives so much praise today because it's the closest the platform has to moderation anymore. If you drive away these volunteers, the platform will descend into 8chan.

I'm not here to dive into Elon Musk's politics, but I have to point out Rupert Murdoch had the smarts to keep his personal views confined to Fox News. You never felt like you were aligning with the right when visiting MySpace or watching The Simpsons. Musk goes out of his way to make Twitter feel like Trump's platform. For many, staying on the platform feels like a political statement, and regardless of one's politics, normal people don't want that drama in their lives. They come to social media for silly memes and cat photos.

I could keep listing examples of terrible Twitter moves, such as burning bridges with advertisers, ill-planned layoffs, and personal meddling with algorithms. It doesn't have to be that complicated. For many people, myself included, Twitter just stopped being fun.

So where do you go? We have three Twitter replacements with different perspectives on what Twitter actually was.

Option 1: Mastodon

Mastodon views Twitter as a public utility. Launching in 2016, this non-profit thinks Twitter should function like email, where no central entity controls everything. You don't sign up for Mastodon through the organization itself, but a Mastodon provider ("instance"), just like you sign up for email through Gmail or Yahoo.

Anything decentralized is a bit more complicated than the centralized alternative. It made sense that in the 90s, America Online was America's introduction to email. That said, I don't think Mastodon is doing a bad job streamlining these concepts. My issue is that the product itself is too unpolished, surprising no one who has ever tried an open source consumer product.

As such, Mastodon fosters a vibrant community of people comfortable setting up WiFi on Linux. As a developer, that's fine, I'm among my people, but there is zero chance that my nontechnical friends will join. It's a shame, because Mastodon is the only platform earnestly trying to decentralize things.

With close to a million active users, Mastodon's modest success should have been a canary in a coal mine for Twitter. When this many people are willing to endure such a rough experience, you know you are on the cusp of an exodus.

Option 2: Threads

Facebook's Threads is more Facebook than Twitter. Yes, you can follow people, but you are force fed an algorithmic timeline that includes people you don't follow. Facebook interprets Twitter as nothing more than an endless dopamine factory that only exists to waste your time.

When you sign up, Threads pulls recommendation from your Instagram follows. This helped blow up the place overnight, but it turns out Instagram influencers should be seen, not heard. For example, because the algorithm boosts posts with tons of replies, every post in your feed is a low-hanging question that could be answered by a Google search.

If I had to summarize Threads' vibe in one word, it would be, "annoying," and it seems Facebook came to the same realization.

I'm not against an algorithmic timeline as an option. It's a fun onramp for new users, before they've built out a meaningful interest graph. Even power users find value in algorithmic feeds that surface great posts they missed. But Facebook's algorithms serve itself, not its users.

Last winter, the algorithm began surfacing bigoted posts for some reason. Facebook fiddled with knobs to make it disappear, but this wasn't about taking a stance on the issue. Threads deemphasizes anything controversial, including politics and news. Facebook envisions Threads as a milquetoast platform for promoting brands, which means it can never live up to the global town square.

Option 3: Bluesky

Bluesky successfully recreates a lot of Twitter's vibrant, weird, funny community. They're doing everything right from a product perspective. They have a polished user experience. They offer both a chronological feed and an algorithmic one. They get how to grow an interest graph, with features like Starter Packs quickly connecting new users to their interests.

Twitter owes a lot of its culture to its virality at South by Southwest 2007, and Bluesky's early community had a similar mix of artists and fun weirdos. With its recent surge of users, Bluesky seems to have broken out from those early-adopters, and now sees established press and celebrities hopping on board. One by one, sub-communities like Scientific Twitter, Black Twitter, and even Tabletop Twitter are making a transition. This is incredible for a service that officially opened signups less than a year ago.

I enjoy Bluesky the product, but I have reservations about Bluesky the venture-backed, for-profit corporation. For example, it was formed by cryptocurrency people and maintains deep ties to the cryptocurrency world. Their initial investors include Protocol Labs, who created a failed, slow, and broken distributed filesystem that only succeeded in pumping its companion token, FileCoin. It peaked around $191, and now trades around $5. We owe a great big "Thank You" to the FileCoin bag holders who helped fund Bluesky.

Bluesky follows the classic crypto marketing strategy of rallying users behind a cause while downplaying their profit-driven motives. They make a big deal about filing as a Public Benefits Corporation, which means next to nothing.

Bluesky claims to be billionaire proof, which is either hopelessly naive or deliberately smarmy. Claims that their platform is open and decentralized are mostly bullshit. Nothing prevents the company from cutting off access to the network, just like Twitter did to third-party clients, and the option of spinning up your own Bluesky clone means nothing when the value a social network is the users and their network effects, not your tech stack.

You're welcome to think I'm overly cynical, but when someone talks like a grifter, builds like a grifter, and raises money from grifters, they deserve all of the scrutiny of grifters.

Even if you give them the benefit of the doubt, Bluesky has raised $23 million to date, and they will need hundreds of millions more to reach Twitter scale. Along the way, they will have to cede more and more control of the company to investors. Those investors eventually expect returns.

Bluesky's upcoming experiment with subscriptions might make a few bucks at its current scale. Long term, they won't make a scratch in the ongoing capital expenditures that come with operating at Twitter scale. When the time comes to monetize, they'll either go with ads or pump and dump a "BlueskyCoin."

But let's get real: most people don't care about technology or corporate governance. From a mass-market perspective, Bluesky is more fun than Twitter and friendlier than Mastodon. That's why it's blowing up. Worse is better.

Bluesky may follow the same path that destroyed Twitter, and we may have this very same conversation fifteen years from now, but that's a pretty good run. You adopt a pet accepting that someday it will die. Don't focus on how it ends. Make the most of the time you have.

The Post-Twitter Era

What will become of old Twitter? The exodus will eventually subside, but its troubles have only begun. The competitors don't need to win over Twitter users to destroy Twitter. They simply need to take a bite out of new Twitter signups, and then the site will decline due to natural user churn.

Paradoxically, fewer users also improves its chances of survival, as the site gets cheaper to run. If it can overcome its $13 Billion in hung debt, it might live on indefinitely as a hobby for Musk, just like Bezos and the Washington Post.

While I think Bluesky will win, it won't reach the same cultural relevance of its predecessor. Twitter was a relic of a begone era, when everyone was still figuring out the social media landscape. For a hot minute it felt like Twitter and Facebook could be the only two networks in town.

We now know that could never happen. Even with the world's greatest growth hacks, the world's smartest algorithms, and the world's most famous celebrities, an interest graph built around short messaging is still pretty niche. It doesn't have the same mass-market appeal of Instagram and now TikTok. Twitter may be where news broke, but that influence would always outperform its active user count.

If Twitter leaned into that reality, it might have faired better. Instead, it tried to be another Facebook, when there was already a Facebook doing a fine job as Facebook. I feel like the operational problems at Twitter were exacerbated by its pursuit of growth, as it prioritized engagement over value.

I resigned from the company 2014, so I don't know what happened in the last ten years, but it felt like growth went hand-in-hand with the rise in toxicity. Quote tweets may increase engagement, but they also encourage dunking and dog-piling and the main character.

At Twitter, the VIT ("Very Important Tweeters") team was proud that this was the only platform where celebrities refused to give their account passwords to their managers. Tweets used to feel like an honest expression of the poster. I think we lost this rawness as the platform descended into toxicity. It's just too risky for cultural icons to show their true selves, anymore.

Watching Bluesky tackle these product problems head on gives me a sense of hope, but what if it's just a bandaid? Maybe when you put everyone in the world's largest chatroom, it incentivize the worst behavior, and any network that achieves Twitter scale is doomed to scatter users like a Tower of Babel.

Maybe the next great network is Bluesky. And Mastodon. And Goodreads, Strava, Letterboxd, Glass, a hundred subreddits, and a million micro-communities spread across the Internet. Maybe this fragmented social landscape is a good thing.

My life has gotten dramatically better in the last two years. I focus more time on our products, and that's lead to some of the biggest launches in the history of our company. I might owe our 50% increase in revenue to cutting back on Twitter.

I still post online, but I've branched out. I share thoughtful, long-form content on this website and my YouTube channel. I share nerd hot-takes on my Mastodon. I post announcements on BlueSky, alongside my experiments in analog photography.

When I resigned from Twitter ten years ago, it felt like much more than just leaving a job. I made some of my best friends at that company, and I knew life would take us on different paths. It turns most of those connections persevered through to this day.

Sometimes I wondered if I made the wrong career decision. I worried my time at Twitter would be the only thing people would remembered me for. I was wrong, and today most people know me for my work that came after.

Death is an important part of life. We, as a species, cannot evolve without death. Your body replaces every cell in your body every seven years. Every seven years, the old you dies. Death doesn't have to be scary. It can also be a chance for rebirth. Try to make the most of it.